Tuesday July 30th, 2024

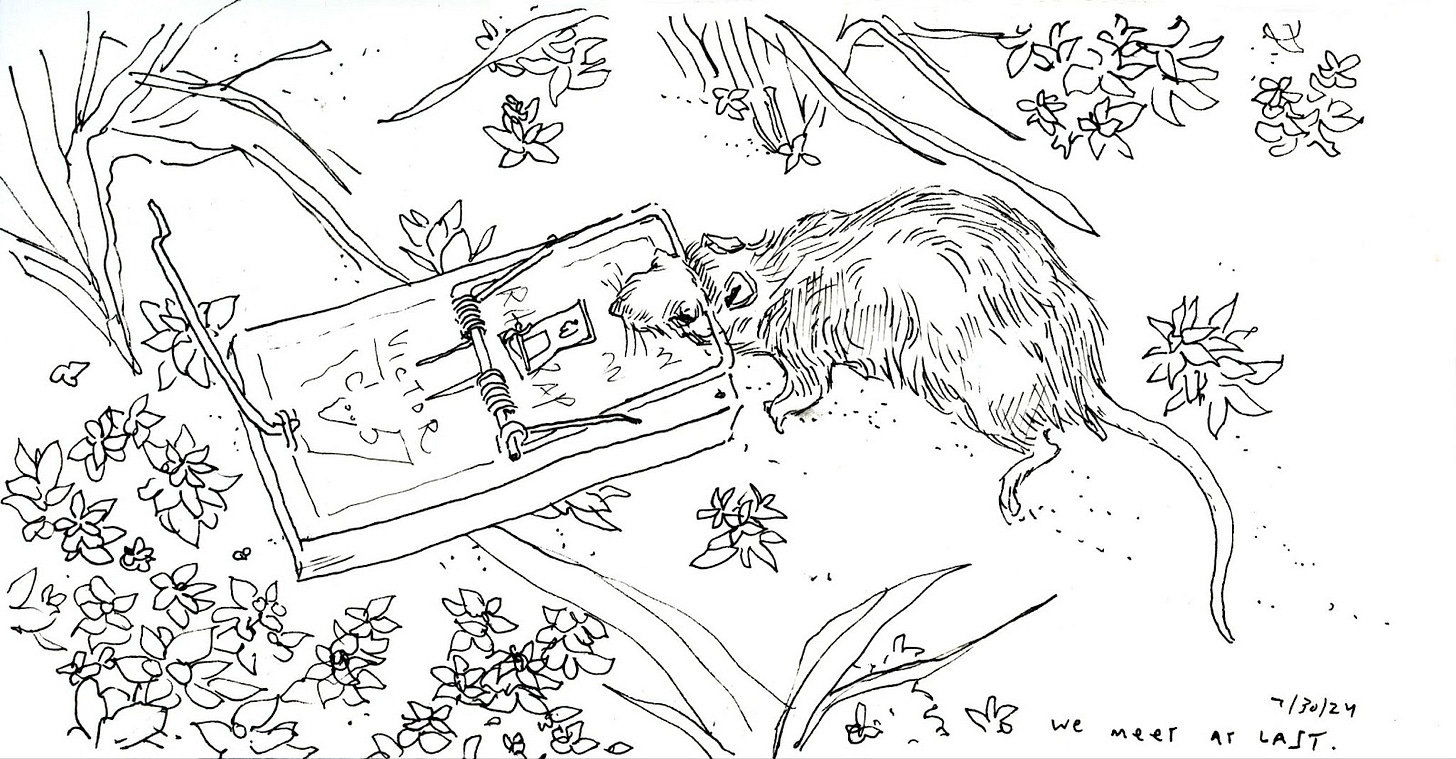

Today is the last full day on Great Sitkin. I slept badly, the chill seeping through the porthole in my bunk. We’ve been lucky with the weather, but a cold cloud has sunk over the island and I am feeling a little trepidation as I eat my eggs. Today we will collect all our rat chews, traps and cameras from the islands we scattered them upon on Sunday. I am finally going to see a rat. Probably.

It’s been a joke to me, this ratless Rat Cruise that became a Slug Sail. “I want rats!” I say. “I want a bag of rats!” Mike assures me I will get some - Sitkin is teeming with them.

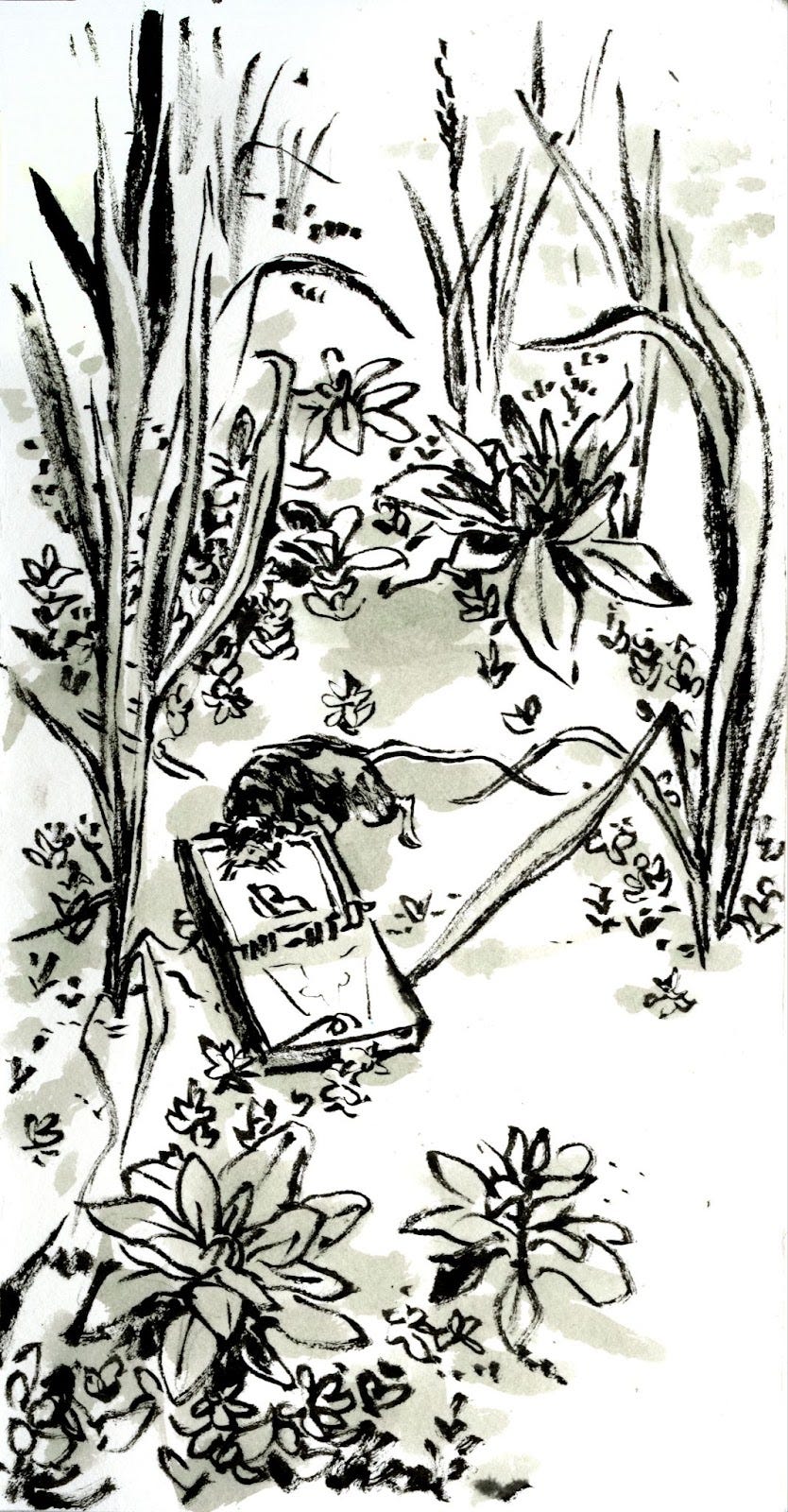

And you can tell. The island is eerily quiet, missing the birds we see and hear in places where rats are not eating their eggs. We head for the traps Katie, Mike, Erica and Adrienne laid earlier.

Stacey finds the first rat. It’s not even in the trap - it’s next to it, curled up under some leymus grass with its paws over its face. It’s suddenly not funny at all, seeing an animal’s suffering.

I draw one, and it’s a strange bleak moment, sitting on a beach on this island covered with the visible signs of human harm, drawing an animal that also does incredible amounts of harm.

Rats likely came to Great Sitkin in the 1700’s. They’re incredibly smart, prolific breeders, and ravenous - they cannibalize each other when food is unavailable. You can identify their tracks on a beach by the straight, purposeful lines in which they move. The biologists that deal with the rats have respect for these animals, and none of them enjoy taking a life, but they are also very aware of the death and disease that they spread. Seabirds are an incredibly vulnerable population, with approximately 30% at risk of extinction from invasive species impacts.

And a healthy seabird population is important. Their migrations connect land and water over thousands of miles. Their poop fertilizes plantlife on otherwise inhospitable rock, preventing erosion and creating habitat for other creatures. Their diet is an insight into the health of our oceans - the stomach contents of a puffin tells you about the fish population far out to sea. Gulls and cormorants eat sea urchins, keeping an often invasive population in check.

Once rats are removed it can take a while for the benefits to show. Some seabirds take several years to breed after they fledge, so it takes time for populations to recover. But the effects are quantifiable, and even extend to the health of the intertidal zone (kelp forests). A study has shown that when gull and oystercatcher populations do recover after mammal eradication, they eat invertebrates that would otherwise overrun the kelp. And healthy kelp keeps on rippling positively through the food web in all the ways you can imagine.

So. Back to the dead rats.

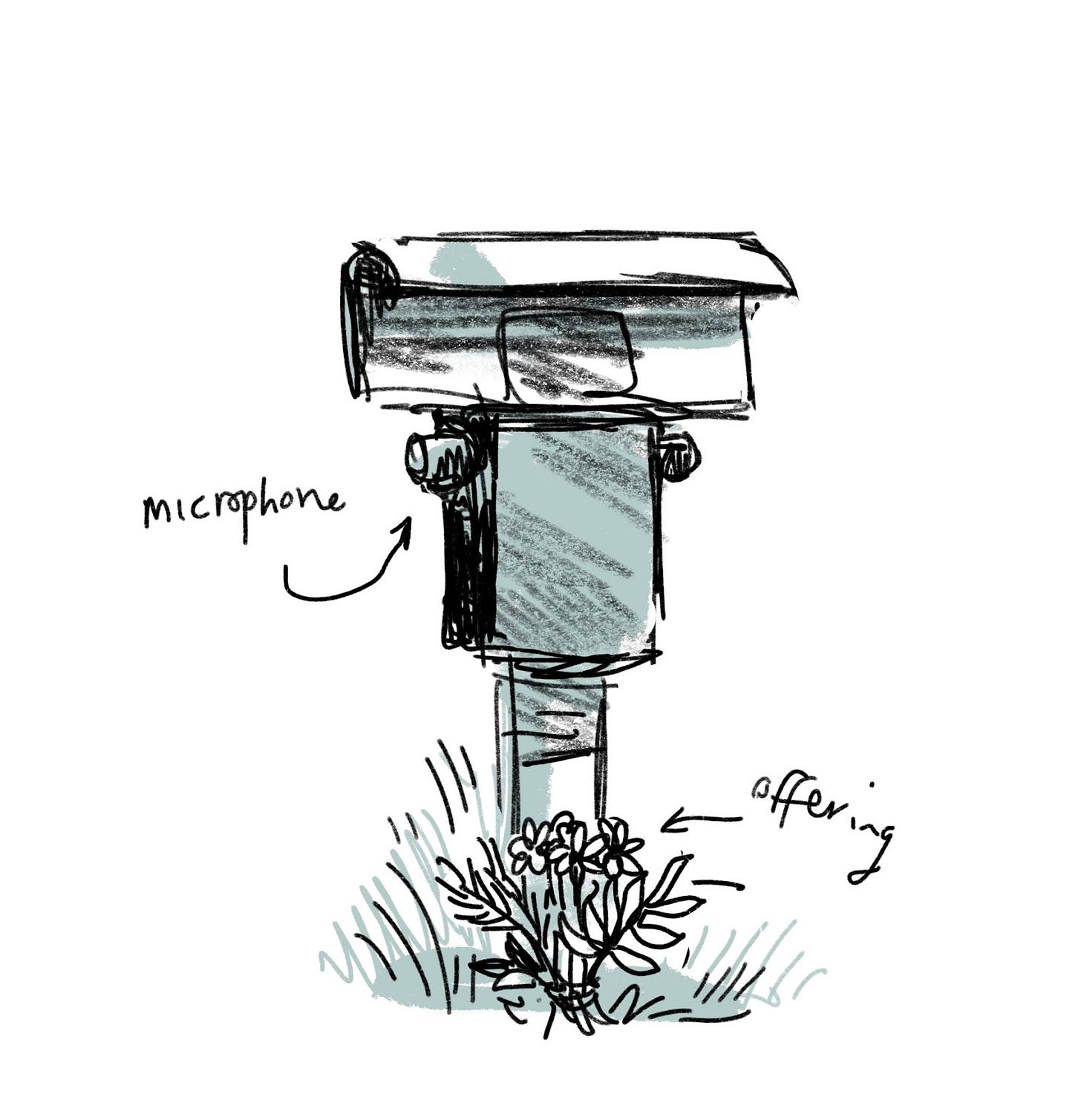

We put them in a bag (they’re going to USDA APHIS to help develop an eDNA detection tool), collect all the peanut butter chew blocks, and our work on the beach is done. Stacey and Ray have one more Great Sitkin task - to set up a song recorder.

It looks like a little birdhouse, with a battery and small microphones. In April it will turn on, and record the songs of the passerines (songbirds) that will be back on the island to breed. This will give us more population data when they collect the recorders. Hopefully the device will survive the long hard Aleutian winter - they’ve been leaving a little offering with each recorder for good luck.

We have time for a hike, and Ray and I explore one of the giant rusted fuel drums, of which there are 26 that we can see from our high spot overlooking the valley. He knocks on one and it’s ominously hollow-sounding. The ground around it is black and reeks of diesel.

Ray has a side hustle of catching bees, collecting samples on these remote islands for DNA testing. He’s also what I would categorize as a giant softie, so I can see him struggling. But he’s also darn good at it.

Katie, Stacey and I explore further, hiking through thick wildflowers and down a steep slope to find a submarine net, put out by the US Navy to catch the small Japanese submarines in the waters off Sitkin. It’s been left in a giant heap in the grass, now a rusty home for Pacific wrens. A… subma-wren net, perhaps??? No? Okay.

I feel a little overwhelmed, looking at all of this and trying to find meaning. The rats aren’t supposed to be here, but where are they supposed to be? They go where we go, and we certainly shouldn’t be here either. That is very obvious from this island. Previous generations have done incredible harm, to nature and to each other, and we’re continuing to do more. But it’s heartening that at least part of the government and its employees are putting resources into repairing it.

And there are simple things citizen scientists (like me!) can do to help, like crab surveys. Green crabs were first identified in Alaska thanks to a citizen finding and reporting one on a beach. As we head back to the beach we squeeze in one last crab survey. I think I’ll be doing these on every beachwalk for the rest of my life. If you want to you can too.

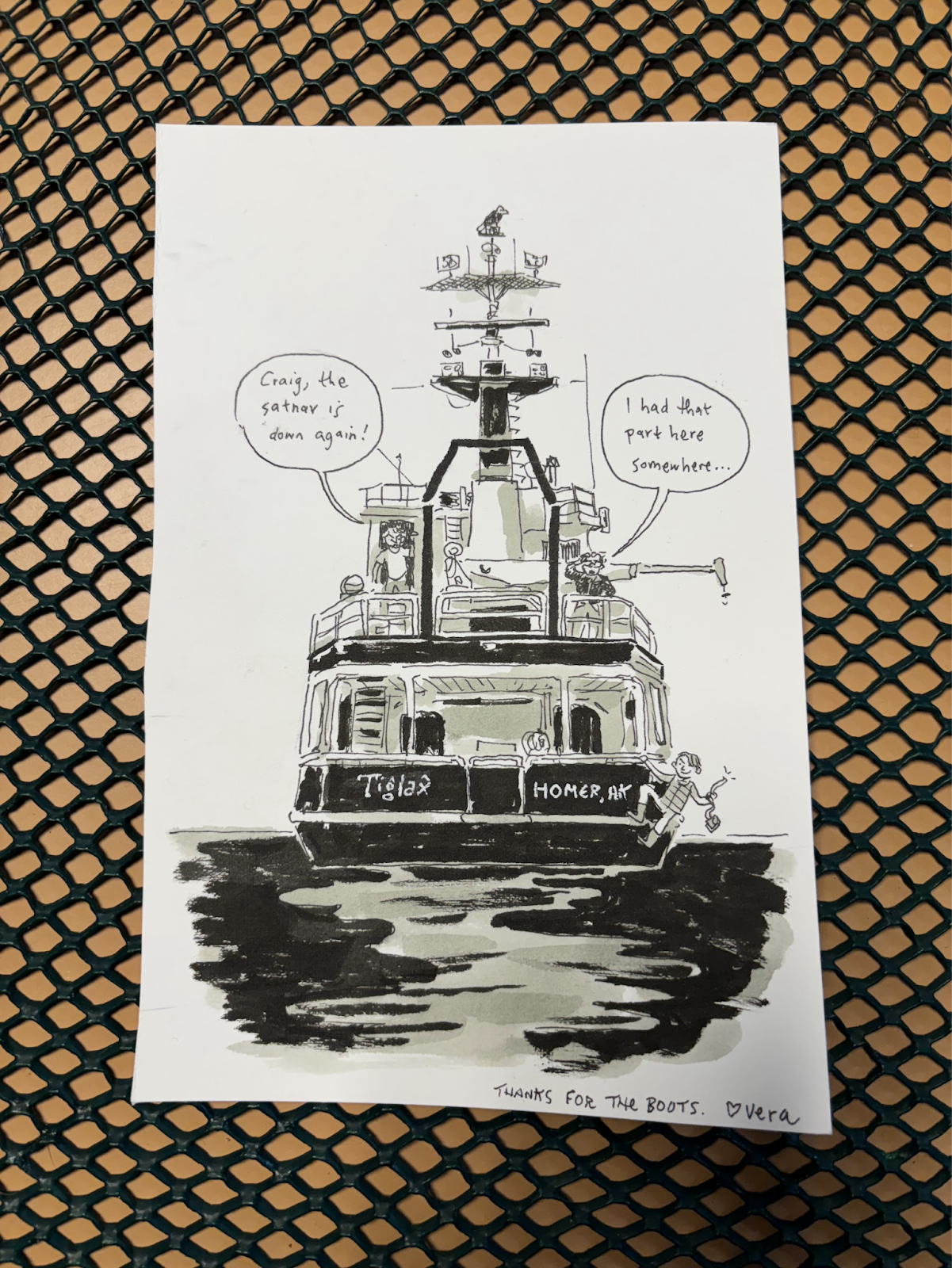

We head back to the Tiglax for tacos and chocolate pudding and start moving away from Great Sitkin. I made a thank-you painting for the Tiglax, and a drawing for Captain John. There is a running joke that I’m the Russian gremlin responsible for anything and everything going wrong on the ship, and it’s the least I can do to apologize.

After dinner I do one last “art show” for the crew, sharing my paintings and sketches with everyone in the galley. I feel like I just scratched the surface of the places we’ve been, and I’m not done drawing - I still have to make a final project to reflect the residency. But making these doodles and notes along the way is going to help me remember. And maybe it’ll help the team remember too.

Late at night we finally pull into Adak Island, our last stop. I get a look at it from the deck at 11pm. Tomorrow’s gonna be interesting.

So wonderful to read another post! This series has really given me an appreciation and interest in things I’ve never thought much of before. 👏🏼👏🏼👏🏼

I love these posts. I heartily hope you continue them in future when the Rat Cruise material inevitably runs out!